A Comparison on Gender between Chinese Language and Greek Language and Gender Issues in Chinese Language

Before starting

This article (aka 小作文) is for my final exam of my linguistics class originally. I chose this topic because I thought that I may not be able to write about it after this time. Later, I decided to post it on my blog because I thought it was a topic worth discussing. Although I know that no one would enter my blog, I still wish those who see this article could rethink those gender problems in the language we speak every day because language is part of our daily life. Language changes can actually help improve this situation.

Personally, I want to thank everyone who helped me. Those who have always stood by me, especially the one who assisted me in correcting the grammar errors.

The Chinese language is a typical genderless language. The Greek language is a typical fully gendered language. The comparison of these two languages can give us a better understanding of how grammatical gender and even gender itself work in a language, leading us to gender issue, an existing problem in China, and how it exists in Mandarin.

Grammatical Gender and Natural Gender

It is obvious that ‘Grammatical Gender’, which is a classification for nouns, is not the same as ‘Natural Gender’. It is also obvious that the Greek has endings to show grammatical genders, which the Mandarin does not have. Therefore, when people talk about gender in Greek, it always refers to grammatical genders, but in Chinese, it always refers to natural genders.

Structure

Pronouns

The most common way to specify one’s gender is to use pronouns.

Pronouns in Greek (nominative, single)

| 1 | 2 | 3 (masculine) | 3 (feminine) | 3 (neutral) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| εγώ | εσύ | αυτός | αυτή | αυτό |

Pronouns in Standard Chinese 1

| 1 | 2 | 3 (for male) | 3 (for female) | 3 (inanimate and animate) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 我 | 你 | 他 | 她 | 它 |

Both Chinese and Greek have different genders in pronouns, however, ‘他’, ‘她’ and ‘它’ sound the same (Pinyin: tā). The character ‘她’ dates back to 1920. In order to translate the English word ‘she’, Liu Bannong introduced and discussed the word ‘她’, which was accepted by the society later.

Since this phenomenon is new, then how about the dialects, for example, Cantonese:

Pronouns in Cantonese

| 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|

| 我 | 你 | 佢 (LSKH Jyutping: koei5) |

In fact, the character ‘姖 (LSKH Jyutping: geoi5)’ does exist, and some people do want to use it like a Cantonese version of ‘她’. However, it is never accepted. Most Chinese dialects have only one third personal pronoun, like ‘伊 (Qian’s Pinyin: hhi)’ in Wu Chinese. They do not distinguish, neither in writing nor in speaking.

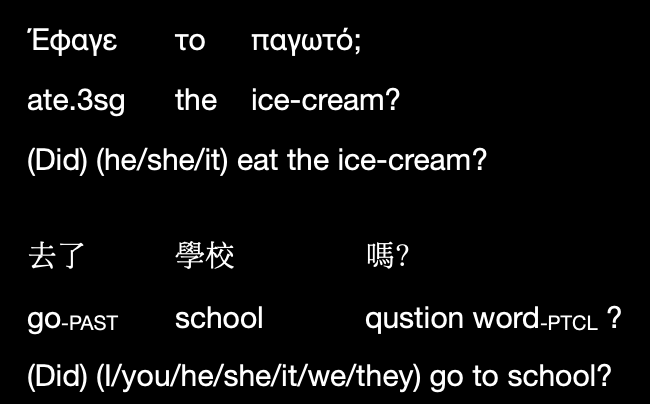

However, there is one feature that both the Greek and Chinese languages share, the pronoun-drop. This is the most common way to not specify a gender. For example:

Nouns

For nouns in the Greek language, most of the time the natural gender is the same as the grammatical gender, which can be distinguished from endings, like if it is ended with ‘ς’, probably this is a masculine word; with ‘α, η’, it should be feminine; and with ‘μα, ο, ι’, it is neutral.

For Mandarin speakers, to declare a gender is easy. People simply put ‘男 (Pinyin: nán)’ for male and ‘女 (Pinyin: nǚ, IPA: /ny²¹⁴/)’ for female. For example, there is ‘男教師 (Pinyin: nán jiào shī)’ for a male teacher, and ‘女教師 (Pinyin: nǚ jiào shī)’ for a female teacher; if there is an animal, it changes to ‘公 (gōng)’ and ‘母 (Pinyin: mǔ)’, like ‘公貓 (Pinyin: gōng māo)’ means ‘male cat’ and ‘母貓 (Pinyin: mǔ māo)’ means ‘female cat’. In grammar, no one knows the gender if it is not specified.

Characters

A single character is able to show the gender. A character usually has a semantic part and a phonetic part. For example, the phonetic part of ‘他’ and ‘她’ is the same. The semantic part ‘亻’ means person, not only man, but the semantic part ‘女’ only means woman. This is why ‘她’ can mean ‘she’, and ‘他’ is originally a general pronoun.

It means that in the Chinese language, although there is no grammatical gender, it can still have the meaning of degrading women, as many characters with the semantic part ‘女’ are usually pejorative. There are some examples:

妒 (Pinyin: dù): (a woman) to be jealous of another woman

奴 (Pinyin: nú): slave

姦 (Pinyin: jiān): (n.)evil; (v.)to rape

However, it does not imply that characters with this semantic part always have a pejorative meaning, such as the character above ‘她’, or show female figures, such as the character ‘如’, which usually means ‘as if’, has no even female meaning.

Gender Issues

In fact, the Chinese language, and the Greek language share some of the same characteristics, like ‘male as norm’ in society. Most of the time, it is not a part of grammar but a part of parole.

Inside Pronouns

The character ‘她’ was a significant part of the New Culture Movement, as it helped women’s liberation and the feminism movement at that time. With the same pronunciation, this character became popular, defeating the word ‘他女’, which borrowed from the Japanese word kanojo (彼女, 彼 (kano, his) + 女 (onna, woman)) and the word ‘伊 (Pinyin: yī)’, which was the first word for ‘she’.

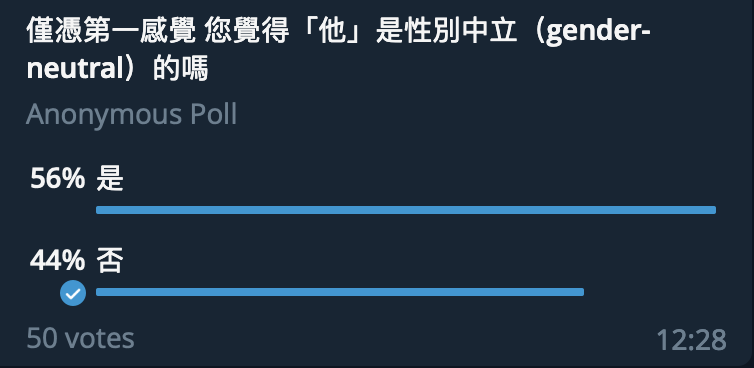

However, the reality is not always like the theory. To know the actuality, a vote was set to investigate if ‘他’ is still considered as gender-neutral.

(Picture: The result of a not very precise survey)

Random 50 people attended, and there are 44% (22 people, including me) people, almost a half, think that it is not gender-neutral. It means that the character ‘她’, being affected by English, actually took the feminine meaning from the original character ‘他’, which became the pronoun for males in parole, losing its neutrality but still being general in syntax, plus the ‘son preference’ issue in China, which still exists in China, causing the problem of “male as norm” in Chinese pronouns.

Fortunately, more and more people realise this problem, and ‘TA’ have been created for neutral usage. This expression comes from the sound, as all third personal pronouns sound the same. The expression becomes popular among the Internet.

Inside words

In semantics, the word ‘unmarked’ usually refers to a basic word, usually the one without any affix, or the one can refer to a whole group. A paragon is the sentence everyone uses ‘How old are you?’. When someone asks, it is not suggesting that ‘you’ are old or young. However, when someone ask ‘How young is Henry’, definitely the one is implying that Henry is young. In the contract ‘old’ and ‘young’, ‘old’ is the unmarked one, as it can be used in both meanings, meaning it is ‘neutral’.

During 2020, ‘πρόεδρος or προεδρίνα’ received a lot of attention in Greece. It shows that in Greek, the masculine form in the unmarked one. The situation is the same in Chinese: in Chinese, if a specific gender is not given to a word (especially occupations, titles, etc.), most of the time the word refers to male. In other word, the unmarked form is not such gender-neutral as what people think in Chinese. Τheoretically, a word in Chinese should be neutral. However, because of the influence of ‘male as norm’, in reality, an unmarked word, of course which can be marked with ‘男’ or ‘女’, usually refers to male.

In 2014, a Taiwanese politician, Lai Pin-yu, who participated in the Sunflower Student Movement, becomes ‘太陽花女戰神’, which literally means ‘Sunflower goddess of war’, on the Internet. The word ‘女戰神 (Pinyin: nǚ zhàn shén)’ literally translates to ‘goddess’. However, just like above, the form is not the same in Chinese. This compound word consists of ‘女’ and ‘戰神’. Using the unmarked form, it is ‘woman’ and ‘god of war’. Her reply showed the same opinion: ‘Why was “women” added? You calls Huang Kuo-chang “god of war”, calls Lin Fei-fan “god of war”. Why calls me “women god of war”? I think this is because women are assumed to be weaker, so when they feel you are different, they will specifically show that you are female. 2’

Inside curse words

While talking about gender issues, those curse words are unavoidable. There is no example here because the characters can tell everything.

In Greek, those curse words do include masculine and feminine forms. They even have these words in neutral.

Suppose that there is a category of curse words in the Chinese language; unfortunately, the words with the meaning of degrading women will be considered more like a bad word. The word can directly point to women or includes the characters which usually have the semantic part ‘女’, like what we have discussed above, inside the structure of characters.

Like what is mentioned in the book Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things, ‘social stereotypes can be used to stand for a category as a whole’. It comes from the internals of a culture: the issue of son preference, the discrimination of women, even the objectification of women.

Is Mandarin really a gender-neutral language?

The answer could be ‘yes and no’, as it depends on how people use this language. ‘No’, it is because all problems above; ‘Yes’, because originally it should be a gender-neutral language and there are so many people use it gender-neutral. For example, when a Mandarin speakers mention a random ‘flight attendant’, as the flight attendant is always considered a female occupation in China, they will always say ‘空姐 (Pinyin: kōng jiě)’, the abbreviation of ‘空中小姐 (lady in the air)’, with the character ‘小姐 (lady, Pinyin: xiǎo jiě)’ gives the meaning of female. Some people prefer a more neutral and formal word, ’空乘 (Pinyin: kōng chéng)’, the abbreviation of ‘空中乘務員 (attendant in the air)’.

There is no other way to solve the problem than to examine the culture and society itself. Fortunately, we can notice the progress. As the language is constantly changing, we can anticipate a more friendly future with a more friendly language.

Notes

1 Standard Chinese is Mandarin used in Mainland China. There is also Taiwanese Mandarin, which has slight differences with Stander Chinese.

2 《台灣女性參政遭遇挑戰:從性羞辱到婚育觀》, BBC 中文, 原文:「為什麼要加一個女字?你會叫黃國昌戰神,叫林飛帆戰神,為什麼叫我女戰神?我覺得背後就是預設女性應該是比較弱的,所以當他們覺得你不一樣的時候,還要特別標注一下你是女的。」

Further Reading

George Lakoff, (1987) Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal About the Mind, University of Chicago Press

刘半农, (1920) “她”字问题, 时事新报·学灯.

黄 兴涛, (2013) “她”字的故事——女性新代词符号的发明、论争与早期流播, Higashi ajia ni okeru gakugeishi no sōgōteki kenkyu no keizokuteki hatten no tameni, International Research Center for Japanese Studies, pp. 125-159.

David Moser, “Covert Sexism in Mandarin Chinese”, Sino-Platonic Papers, 74 (January, 1997).